Jimmy Thompson

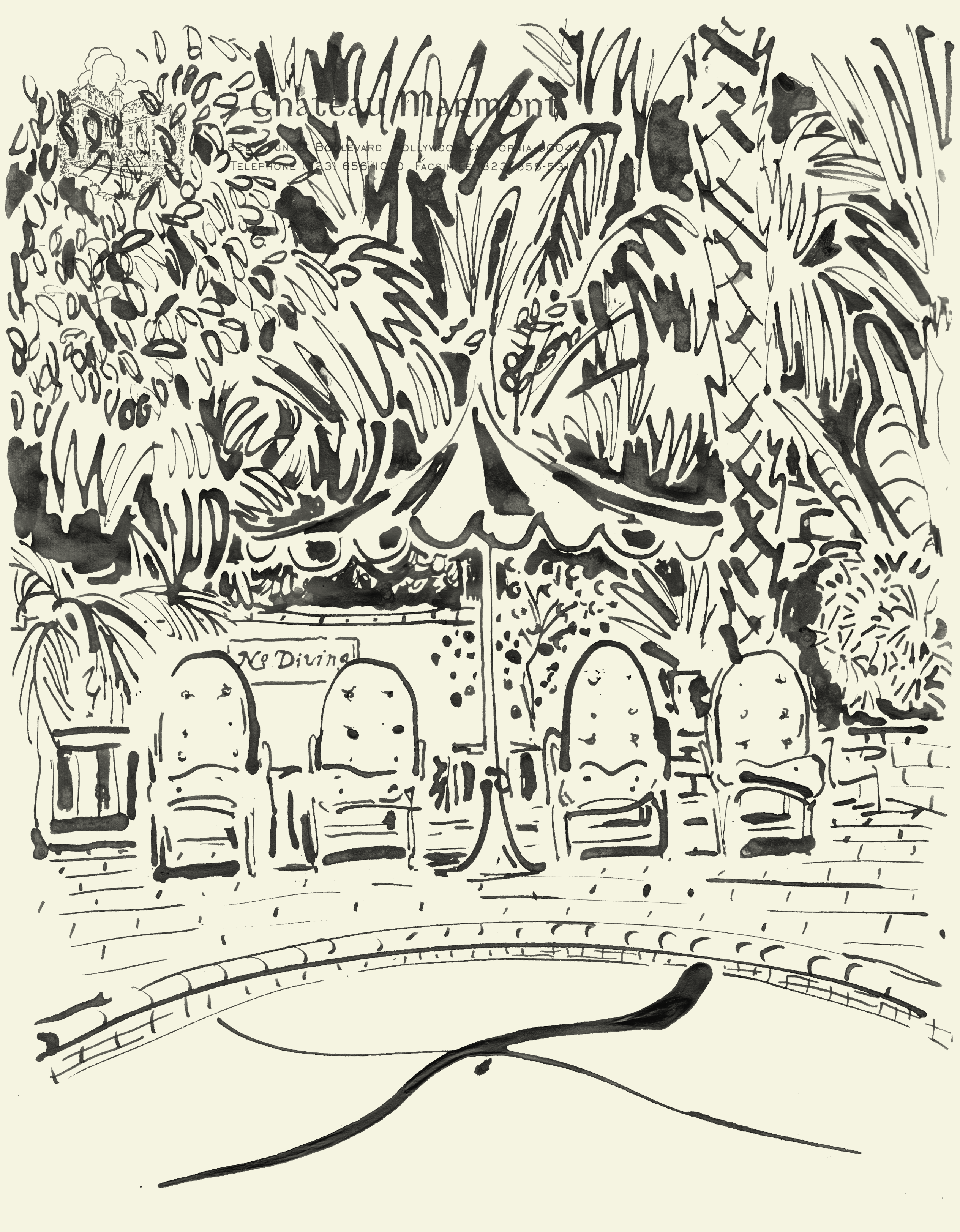

Jimmy Thompson is as Californian as they come. He came in to do the interview with dark glasses and a casual smile. He often finds himself sitting poolside at the Chateau Marmont, drawing a timeless world, a Los Angeles before they cut the hedges and the mystery disappeared. Jimmy’s work pays homage to the great nineteenth-century impressionists. His drawings of cafés and roof- tops remind us of a young Derain or Matisse. He has the ability to capture someone’s essence in a few quick strokes - some may say this style reeks of confidence, but we think it is instead a tenant of Jimmy’s authenticity.

How did you initially find drawing?

I always got encouragement from a really young age. I was good at drawing, but I guess after high school I felt more strongly about it. I wasn’t good at math or any of those other things, and so I thought, This is the hand I have to play with.

Looking at your drawings of people, it’s almost like you don’t fuss with it, you just lay ink down and depict somebody’s face in a way that’s not overdone.

I’m glad you said that, because I’ve been accused of sometimes being too simple. But I think that’s my goal, if you can distill something to its essence, then you move on. I did all that rendering stuff when I was in high school AP courses. If you can capture a simple gesture, the way your arm just hit, or similar lit- tle key moments, then you have it. You don’t have to do every button.

It shows mastery. If you look at what Matisse was drawing towards the end of his life, he could get the arch of a woman’s back in just one line.

It reeks of confidence, he got to a place where he didn’t have to explain why he did that. The viewer looks at the drawing and goes “Oh, she was standing like this?” It makes you think more.

I love the drawings that you do while out in the world, as casually as while eating lunch somewhere, drawing on the side of a paper menu. There’s a feeling that you may lose it, it may get crumpled up and tossed, but it exists in the moment.

I was having lunch in New York a place called Balthazar, and I was drawing the staff and the people around me. I could tell that a couple of people who worked there were kind of intrigued, I decided I’m just gonna leave. Then I get a message on Instagram a week later saying, “Hey, you don’t know me but my dad works at Balthazar and he took that drawing you did and he is just so proud and tickled that you depicted him in his workplace.” That just made me feel so good because now it has a life of its own. That being said, other times a waiter will just toss it. Other times I’ll pull over while driv- ing, even if I had something to do or someone to see, I’ll just get obsessed about capturing a moment I see. I pick up little things on the street, whether it be a note, someone’s gro- cery list, or just anything. I love cap- turing and making art of little things that maybe I’m not meant to see, or that most people may step over.

It refutes art being this upper echelon thing that only wealthy people can reach. Instead, it’s the inverse. This man was so touched by you drawing him on a napkin. I think it also shows that it’s within you, “you can take away my paper and pens and I can still make what I want to make. I could do it again.” I think that’s a beautiful quality, who taught you that?

My mentor was pretty incredible. He illustrated The Catcher in the Ryecover, his best friend was J.D. Salinger. He was one of the only people that J.D. talked to for the rest of his life. He was in his 80’s still teaching, that was inspiring to me, peo- ple who are still doing it, sharing information. He talked about making things feel cinematic. Letting the viewer’s eye create motion within a still image where you can look around. Purposeful, thoughtful, spontaneous decisions.

I always got encouragement from a really young age. I was good at drawing, but I guess after high school I felt more strongly about it. I wasn’t good at math or any of those other things, and so I thought, This is the hand I have to play with.

Looking at your drawings of people, it’s almost like you don’t fuss with it, you just lay ink down and depict somebody’s face in a way that’s not overdone.

I’m glad you said that, because I’ve been accused of sometimes being too simple. But I think that’s my goal, if you can distill something to its essence, then you move on. I did all that rendering stuff when I was in high school AP courses. If you can capture a simple gesture, the way your arm just hit, or similar lit- tle key moments, then you have it. You don’t have to do every button.

It shows mastery. If you look at what Matisse was drawing towards the end of his life, he could get the arch of a woman’s back in just one line.

It reeks of confidence, he got to a place where he didn’t have to explain why he did that. The viewer looks at the drawing and goes “Oh, she was standing like this?” It makes you think more.

I love the drawings that you do while out in the world, as casually as while eating lunch somewhere, drawing on the side of a paper menu. There’s a feeling that you may lose it, it may get crumpled up and tossed, but it exists in the moment.

I was having lunch in New York a place called Balthazar, and I was drawing the staff and the people around me. I could tell that a couple of people who worked there were kind of intrigued, I decided I’m just gonna leave. Then I get a message on Instagram a week later saying, “Hey, you don’t know me but my dad works at Balthazar and he took that drawing you did and he is just so proud and tickled that you depicted him in his workplace.” That just made me feel so good because now it has a life of its own. That being said, other times a waiter will just toss it. Other times I’ll pull over while driv- ing, even if I had something to do or someone to see, I’ll just get obsessed about capturing a moment I see. I pick up little things on the street, whether it be a note, someone’s gro- cery list, or just anything. I love cap- turing and making art of little things that maybe I’m not meant to see, or that most people may step over.

It refutes art being this upper echelon thing that only wealthy people can reach. Instead, it’s the inverse. This man was so touched by you drawing him on a napkin. I think it also shows that it’s within you, “you can take away my paper and pens and I can still make what I want to make. I could do it again.” I think that’s a beautiful quality, who taught you that?

My mentor was pretty incredible. He illustrated The Catcher in the Ryecover, his best friend was J.D. Salinger. He was one of the only people that J.D. talked to for the rest of his life. He was in his 80’s still teaching, that was inspiring to me, peo- ple who are still doing it, sharing information. He talked about making things feel cinematic. Letting the viewer’s eye create motion within a still image where you can look around. Purposeful, thoughtful, spontaneous decisions.

READ THE FULL INTERVIEW IN ISSUE THREE