Fred Hoffman

Fred Hoffman has worked with so many artists from the past century it is a bit daunting to even try and find the right starting line. Working with cultural titans such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dennis Hopper, Richard Serra, and Chris Burden, Fred has both an eye for great art and an affinity for finding the pulse of a contemporary art movement. From his accounts of conversations with Basquiat, to crafting submarines with Burden, to blowing up Dennis Hopper (unharmed – so to speak) it was all met with the same humility. Fred is a man who has been in many rooms with many of the artists who have defined 20th century American art history. Spend an afternoon with Fred and you realize you could possibly receive more of an education than you might in an entire semester’s worth of exams. Not only does Fred love the work, but he understands it’s part of the greater history of art and the world. When one has touched as many circles as Fred has, sat with creators, and storied the past, they become an artist in their own right. Sitting in Fred’s living room, glancing over the stacked paintings that line the walls of his house, it becomes evident that Fred’s love of art is unending.

interview & photography by

Achilleas Ambatzidis & Finley Jacobsen

Achilleas Ambatzidis & Finley Jacobsen

How long have you been in Los Angeles?

I was born and raised in what is Westwood, then I went to university and came back here in the late 60s, lived in Laurel Canyon in the late 60s. Got very immersed in…

That whole world.

The whole world of Laurel Canyon. (Laughing) I was very involved in the music world at the same time I was getting a PhD, I was involved running the second underground record store in Los Angeles. It was called Music Revolution, it was started by a couple, Les and Susan Carter. He was a white DJ at the jazz station in Detroit. He moved here and was hired to be the program director for the first underground radio station in Southern California, called KPPC, which is a complement to a radio station called KMPX, which was in San Francisco, started by Tom Donohue. Les and Tom really introduced long playing vinyls to the public. Our record store featured a lot of the music that we played on the radio. I realized that I was more suited for the art world than the music world.

What do you think that realization was?

I clearly had a really great instinct even before I was working with artists. I guess, I felt more comfortable around artists than musicians. Les and I used to go to the record distributors to get records, new releases; we would go on Thursday afternoon for the new Beatles or Stones record. We would go to the distributor and get hundreds of copies and sell it for 25 cents over what they cost us and have massive crowds at our record store. We didn’t make any money but we were the hottest thing in the world. Anyway, I felt that the people in the music business were really seedy, fairly corrupt. In terms of what music was getting played, I could see that there was a lot of corruption behind that. Not necessarily the station that Les ran, you could see it in terms of the AM radio, just really sketchy. That’s always put me off.

I don’t think much has changed in that department in terms of music.

Also I was still firmly committed to get a PhD in the history of art. Probably certain parental, not pressure really, but expectations let’s say.

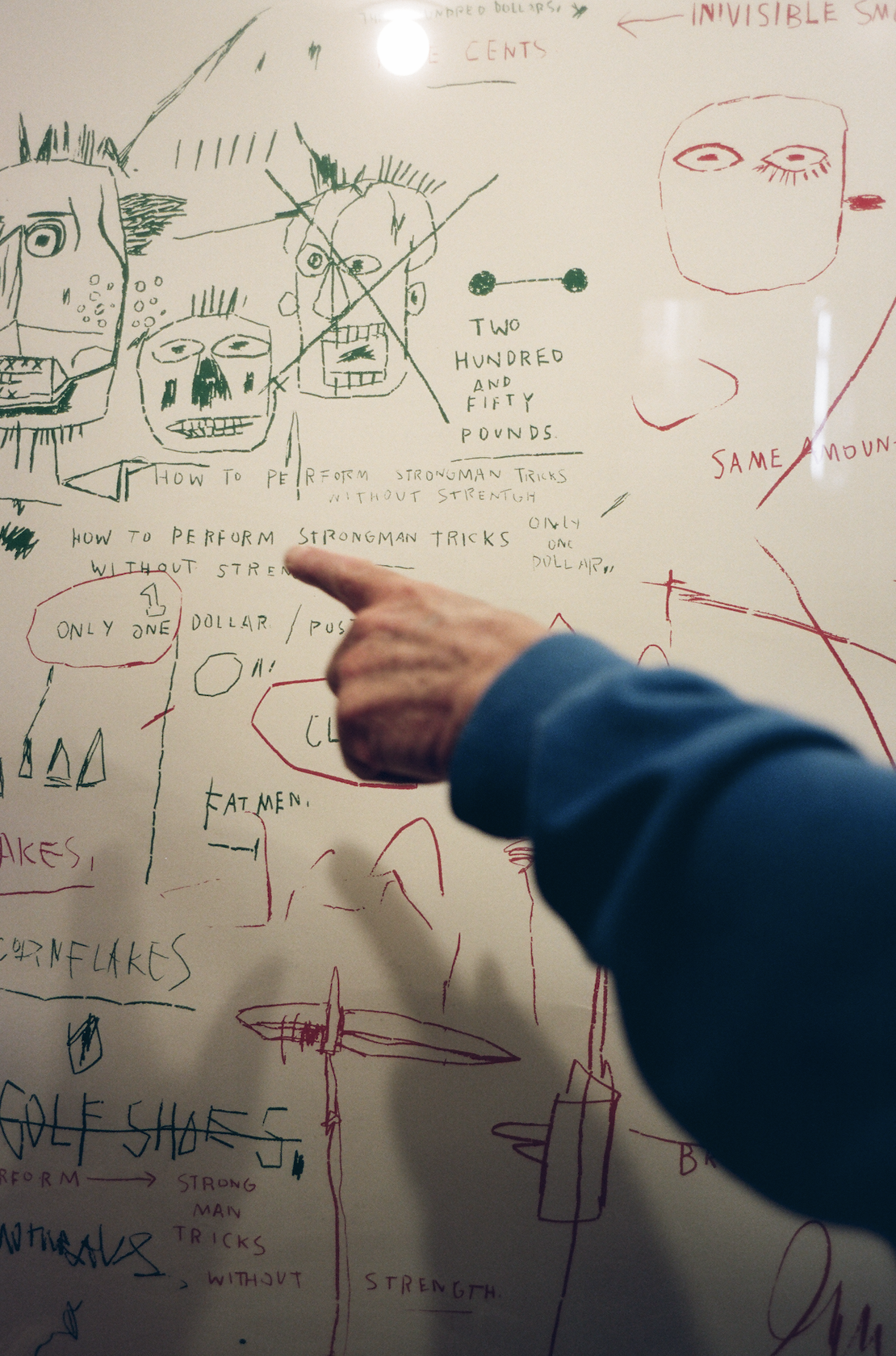

When did you initially become involved with Basquiat, or how did you come to meet him?

I was living in Venice, my business was in Venice, spending time with artists there, we all hung around this one restaurant called the West Beach Cafe, which was on North Venice Boulevard. It’s no longer there. I actually started curating shows there, including Basquiat and Keith Haring, a lot of the New York artists of the 80s. One of the people I encountered through being in Venice was the art dealer Larry Gagosian, this is long before he was this mega dealer. He opened a gallery in Westwood in the mid 70s, it was just showing local artists, but a very good program. He had his first show with Basquiat’s first dealer Annina Nosei, this would be late ‘81 or ‘82 (in New York). He came back to LA, opened a gallery in West Hollywood, which showed Basquiat – that’s where I first saw Basquiat. Later in ‘82 Larry invited Basquiat to come back to Los Angeles to live and work in the ground floor of Larry’s newly completed townhouse in Venice on Market Street. Basquiat came and started living and working there in November of 1982, and he asked Larry if he could connect him with somebody who he could work with within the medium of silkscreen. He had a very clear understanding of exactly what he wanted to do. Larry called me up and said would you come meet him.

Jean-Michel shared with me the idea that he had, and I immediately understood it and related to it. And said, “Let’s go for it.”

It was not an easy undertaking, but I was totally convinced that my new little production business could pull it off. We started working together from that time.

And what was this idea that he had?

He wanted to make a large silkscreen that the final version would be on canvas, it was called “Tuxedo.” It’s a silkscreen that’s approximately eight feet high by four and a half feet wide. That was basically a compilation of drawings, collage and painted crown that he had executed. What he wanted to do was take a series of drawings, photograph them, and then have them reversed through the photographic process, and turn them into reversed acetates. Then hinge all the different acetates together, sort of layout as a grid stacking. The acetates would be exposed transferring the image onto the screen, which then would be printed onto prepared canvases with white gesso. In this process, going from the originals of black drawings on a white background would be reversed to white imagery against a black background. Early on Basquiat was interested in flipping identities, the black man in the white world, the white man in the black world. It’s also a very cool look that he discovered. We executed that over three months. It was a very complicated piece to me, especially getting the registration all correct. I mean, it took four people, two on each side, pulling the squeegee evenly, eight feet. It’s a monumental print.

We went to the show in Downtown Los Angeles, “King Pleasure” we were really kind of surprised because in the tombstone it says “Tuxedo” is made of acrylic and collage.

The edition was an edition of 10 plus the printer’s proof, so actually 11 copies of the work made. I sent a few of them to Basquiat’s studio in New York. Basquiat was asked by the dealer Tony Shafrazi to be included in a show which was called “Champions.” Which was going to be the first major exhibition of downtown hip hop culture, primarily graffiti artists, who were all coming into acclaim and notoriety. This would be their first gallery show for many of these people. Basquiat had already moved from the street to the gallery completely, but most of the other artists in this show were out tagging buildings, subways, whatever. Anyway he asked Basquiat to include a work in the show and he immediately said to me, “I want to show ‘Tuxedo.’” We arranged for the shipment of one of “Tuxedo” on canvas to Shafrazi Gallery in New York. Upon receipt Tony flipped out and called Basquiat screaming at him, “How dare you include a print in such an important show!” Completely misunderstanding the impact of this piece, as did Eli Broad at the time. Who was already probably the largest collector of Basquiat at that time, just for his personal collection. Eli came in, previewed the show, saw and immediately gravitated to “Tuxedo” and said, “I’d like to buy that piece.” I came into the gallery later that day, and Larry’s assistant came up to me saying, “We already sold ‘Tuxedo’ to Eli.” I thought about it for 30 seconds. And I said, “Did you tell them that it’s an edition of 10?” And they hadn’t. I said, “Well, he’s gonna find out sooner or later, you probably should let him know.” As soon as they told him, they canceled the sale. Anyway, then I arranged for that copy of “Tuxedo” to go to Jean-Michel’s studio. I come into town a couple of days later, and I see he’s made a few gestures on the canvas with white paint. But that’s not the version that’s in the show “King Pleasure.” Another version of “Tuxedo,” which I had sent to Jean-Michel, unbeknownst to me, he painted over portions of it with white paint, acrylic, and also collaged original drawings. Turned it into something significantly different than “Tuxedo.” In the end, of the 10 original “Tuxedos,” two of them were altered. The crazy thing is that Basquiat spent the equivalent of two and a third years out of his eight and a half year career/life as an artist in Los Angeles. Even now, the broad public – a lot of people in the art world – have very little understanding of how much a part of his career was the work he made in LA.

At this “King Pleasure” show they had a mock up of his studio. What did you think of this recreation?

One of the funniest things for me is, you know, they mixed, especially in that one room, a couple of pieces that are his most important works of art. On the same token, there’s works in there that I am absolutely convinced he never completed. The reason it’s there is that Jean-Michel never wanted to show it, and nobody that was coming to the studio wanted to buy it, which in some cases was for the best. There was an important painting, “Masonic Lodge,” that was sort of so abstract and oblique, that it actually was never desired by any collectors. In retrospect, it takes a lot of time for people to unravel, really look at the art in depth. Anyway, the funny thing was in that setup, they did have “Charles the First,” which is one of his greatest artworks. They have it lying on the floor. I mean, which is sort of nice in a way that they’re making no qualitative distinctions, but it’s sort of wonky. Take one of the great works of one of the great artists and sort of throw it.

What was that studio like, in reality?

Jean-Michel’s studio was a whirlwind of stuff going on. Both in New York City and the LA studio.

In New York,I couldn’t go hang out with Jean-Michel for days on end, but in LA, I went to the studio a lot that winter. I would go after dinner. I lived in Venice and I would go over there, 8 o’clock, and maybe stay until three to four in the morning. I essentially went on and made, I think, about five other editions with Jean-Michel. But in the studio I mostly just watched, he was very actively engaged when he was focused on making art…So in his mind, you weren’t even in the room?

Exactly. I mean, you really weren’t. You could ask him a question, he may or may not focus on it. If you’re being polite, you would wait until he took a break, and then you could talk. The crazy thing is, I have very little recognition of talking to Basquiat about the meaning of his art. I think he respected me as a PhD in my knowledge of the history of art, and we had a lot of dialogues about art and other artists. But in terms of the meaning of his art, it wasn’t until I was retained by the Brooklyn Museum to curate the last American retrospective that I really started honing in on the depth of the content of his art. You don’t really need to know that to know that there’s a lot going on, and that it has a deep meaning. If you really wanted to focus on it, you could talk about it for a long time. Ironically, when I started graduate school, the professor who everybody was working with in modern art really discouraged any of us from focusing on contemporary art, saying there wasn’t enough content that you could come up with to talk about it. One of my best friends in grad school is one of the most acclaimed art historians of the last 40 years – the world’s expert on Jasper Johns. She fought with him like crazy to write her doctoral thesis on Johns. He was dead set against it. I just always thought about that, if he had been around with Basquiat, he would have said there was nothing to say here. A lot of people in New York, that was their take on Basquiat. There’s nothing to say here. There was only a handful of people that really got that he was part of a long lineage and tradition, and saw him in the lineage with Picasso and Rauschenberg.

When do you think that tide turned? Or do you think that people still don’t really understand?

I think he crossed the threshold now. Call it, “He made it through the gate.” I was as close to Basquiat as almost anybody, and I had a giant wake-up call when I wrote my text for the Brooklyn Museum show. That’s still one of the most important texts on Basquiat. I took five works and really took them apart and went into what they were about. I think I could do that for the rest of my life, take another 10 works, maybe not go into the same depth that I went into with those five, because I picked five of the greatest. It’s a ripe field if someone’s interested.

So much of Basquiat’s work looks and feels free and expressionistic, was there ever any editing?

The funny story there is that after I was hanging out with Basquiat for a while, there were other people that would come to the studio. Larry would come, Larry would bring people to the studio. People understood that I had a really good dialogue with Basquiat, clearly not just professional but we were friends. On more than one occasion, a dealer or a collector would say something along the lines of, “Don’t you think you should go to Basquiat and tell him to slow down, there is way too much art he’s putting out.” So that was one kind of editing there. But I don’t think anybody that really came and sat around for a while would ever say, “Hey, do this and don’t do that.” I saw him start paintings and go 80% of the way to completion and then obliterate 80% of what he had just painted. Take it back to just a small segment and then build it back up. He knew where he wanted to go with paintings, and trusted that it wasn’t going to all be in one hit, even though it looks like it was all done in 30 seconds. Some of the more important paintings, especially, are layers and layers of imagery painted over. There’s a lot of under painting, “Masonic Lodge,” we had it X-rayed, and there’s tons of imagery underneath. That painting, what he was doing in the end was having a dialogue between the top and the bottom layers. Really, he could have a figure down below that was making a certain kind of statement. It would either be negated or complemented by what he put on top. He was confident enough that he knew that there were multiple options or ways to get things together.

On the subject of individuals who knew that there were multiple options to get where they wanted, we recently watched “The Last Film” by Dennis Hopper. Can you talk about your work with him, how you guys became comfortable with one another?

I worked with Dennis and curated a bunch of big shows. I had this little print studio in Venice, New City Edition. Dennis would come by all around the time when Dennis came back to Los Angeles. He’d been living in Taos, after this whole decade of drug debauchery, getting shut out of Hollywood because of “The Last Film,” he’s persona non grata. Slowly, a series of events led him back here, to Venice in the early 80s, and buys one of these three Frank Gehry loft spaces on Indiana Avenue off of Hampton. I’m only a few blocks away with my print studio. I started working with Chuck Arnoldi, and he starts coming by to check out the work we’re doing. We started a dialogue, he would come by and he was crazy, hanging out for an hour looking at four artworks.

Was that when you started to work closer with him?

When Dennis was making “Colors” – which is about the Crips and the Bloods – he started focusing more in depth on graffiti and returned to making paintings. He makes a series of paintings, which are a combination of photographs from “Colors,” images from the film, juxtaposed with a gestural abstract graffiti style painting. When I did a major show with Dennis in 1995, I said, ”Dennis, I want to do a major retrospective with you, bring out everything you’ve ever done.”

What was all of his work?

He made assemblages, photographs, and these paintings. Prior to coming back to LA he did a show in Houston, he did this piece in a rodeo in Houston. It’s a stunt. Basically you build this three walled cardboard structure, and it’s lined with dynamite. And the way the dynamite’s included with the cardboard causes it to blow out. And so he huddled in the middle of it. The dynamite is lit on fire. And everybody’s going bonkers, that’s the end of Dennis. And he comes out unscathed. We turned that into a piece where we put three pieces on a wall, which are two stills from this performance, and in the middle, a white canvas on which we projected the footage of that event. It’s sort of an installation. He then did some large billboard paintings that were blow ups of 60s photographs that were fantastic, 12-14 feet high. But his photographs in the 60s are really important documents, moments in history.

Could you explain how you and Chris Burden first crossed paths?

In the late 70s I came up with this idea to do a big group summer show, called “California: A Sense of Individualism,” sort of a counterpoint to the way that a lot of the art in the 60s was getting, contextualized is one word. In a way, Color Field painting was thought of as the one of the main art forms in the late 60s, to the exclusion of countless artists that don’t fit into any category. With that as a background I put together this big group show and wanted to put Chris in the show, and that started the dialogue. At a certain point, by hanging around each other, he proposed that we would do an edition together, which would be this piece, called “All the Submarines of the United States of America.” He had already made these little surrogate cardboard submarines, handmade. He came to me saying he’d like to make these cardboard submarines, one for each sub that’s been commissioned by the United States since the Civil War. It took two years to make all 625, and we showed them as editions in vitrines. And it was the first LA international art fair that year, the same week that MOCA opened. So we’re showing the subs downtown. I sold a couple of them, but I kept thinking, this is ridiculous, we need to show all the submarines together. So I came back to the studio, called Chris, and said “We’ve got to reverse course here. We’ve got to show all the subs together as one installation.” He said, “I’m on board.” I had to actually buy one that I sold. Anyway, we kept working together; we presented this large piece called “Beam drop Inhotim,” he did it first at Art Park. Then I took the piece and we did a major installation, first in Brazil and then one in Belgium. The idea is a pit 25 by 25 feet about eight feet deep filled with freshly poured concrete that has a slow curing agent, it sets over 12 hours. Secure in advance 125 giant steel I-beams, ranging from 10 feet to 25 feet long, weighing thousands of pounds. A giant crane on the side, picking one beam up at a time raising them 100 feet in the air, releasing them at Chris’s direction and dropping them into the pit.

That is incredible, anyone from the Ferus Gallery that you crossed paths with?

A few, actually when I lived in Laurel Canyon, I lived a block away from Ed Ruscha. Ed and I became friends in the 60s.Ed Moses in Venice, I worked on and off with him, never did a show with him. Larry Bell was there as well. Dennis was basically part of the Ferus group, Irwin and I knew each other, respected each other. I never showed Bob, one of the few artists that I really wanted to show, I never could make it work.

I mean he started going out of the gallery. Because you’ve worked with so many artists in different mediums, was there a point where you discovered how your relationship with artists evolved? Was it always naturally, you gravitated towards certain artists and wouldn’t gravitate towards others?

I think I always first thought about how important I thought the artist was. I had certain opinions, sometimes I was right and sometimes I was wrong. There’s a few artists that I didn’t quite get that in retrospect, wish I had gotten. There were other artists that I think I got that I really didn’t think I would be a good match working with. I was encouraged after doing this big Richard Serra show to work with these artists in New York, some of them I just couldn’t relate to, too conceptual or oblique. It didn’t click, I think that ironically, my whole academic career was focused on painting, but I worked very well with sculptors, I don’t know if it was just that it had more of an edge to it. But I’ve really enjoyed working with artists like Chris, or Richard Serra. It requires a lot, it’s not just picking paintings in a studio, there are certain limits, some artists you would give an inch, they would want a mile. You have to talk them down from some really over the top idea that they want to do. Some I had to walk away, the risk/reward wasn’t worth it. But mostly, if I believed in the artists, I would try to keep the dialogue going and try to engage them.

GRAB THE FOURTH ISSUE

More From Issue Four